Is ChatGPT really your friend?

This article first appeared in our Social Issues Bulletin – Issue 55 which is available to download here.

The story so far

In my first article, I outlined what AI technology is, and what it can do and provided a simple overview of how it works.1 We considered some of the challenges that this technology presents to humanity, especially recent developments in Generative AI like ChatGPT that generates new human like output of text or images based on a text input. We saw how it might challenge our ability to discern truth and reality whilst other automated decision making systems might affect our ability to secure a loan or insurance policy due to bias. In article 2, we set out a Christian anthropology to provide a foundation for our evaluation of AI technology and its potential impact on what it means to be made in God’s likeness, to have dominion and to be made for relationship. We briefly reviewed different perspectives on the soul and whether the mind functions like a computer, issues that have a bearing on whether it might be possible to replicate a human mind and consciousness.2

In this final article, we will explore some key questions that will help us to navigate whether or how we should use the AI applications that are available today and in the near future. We’ll look especially at those based on Generative AI, whether applications that we might find in the workplace like ChatGPT, used in Microsoft’s copilot, or apps developed by Christians to write prayers, sermon outlines, summarise bible books or provide spiritual counsel.

At this point, some might be thinking it’s ok to use any applications of AI, provided that our motivation is good and we don’t use it sinfully, to create pornography for example!

Guns don’t kill people, people kill people

‘Guns don’t kill people, people kill people’, so runs the National Rifle Association slogan in the USA. The implication behind this slogan is that technology is neutral, it’s what we do with it that matters. It is a view held by many people, including Christians and those who develop technology, but is this really true?

Over the last 100 years or so, philosophers of technology have sought to define what technology is and approached it from several perspectives. One perspective holds that an artefact or tool is simply something that extends human capabilities and enables us to accomplish our objectives. Studied from this perspective the emphasis tends to be on how technology enables us and influences our actions. How might the advent of email have altered our writing habits or communication modalities for example, do we use the phone less, and so on? Typically in this light technology is most often seen as offering convenience and efficiency, we can do things faster and easier, not bad outcomes, one might think.

Other philosophers have argued that this is too narrow a view of technology and that we need to understand the values that lie behind the design and development of a tool, and indeed how tools shape societies as they are used. Some would go further and add that it’s also necessary to understand how we got there, and what conditions predisposed designers to think such a tool was necessary in the first place. They would argue that technology doesn’t just appear, there are choices to be made, influenced by economics, culture and politics.

The development of the timepiece provides a simple illustration of how technology shapes humanity. Before the invention of the clock, cultures were mostly event driven – I get up at dawn or eat when I’m hungry. The timepiece gradually changed Western cultures into ‘doing’ cultures driven by productivity and efficiency and our lives are now scheduled by the clock. Continents like Africa have retained more of a ‘being’ culture that values relationships and events more than units of time. Which is best? Having worked in both cultures there are benefits and disadvantages to both, perhaps the answer lies in finding a God honouring balance that best reflects who he is.

Although technology shapes us, it doesn’t necessarily do so in a completely negative way. The late philosopher of technology, Don Idhe, suggested that technology has both an amplifying and reducing effect. This idea can be easily understood when we think about how a telescope enables us to see far distant planets yet at the same time it narrows our field of vision. Few would argue however that the amplifying benefits of a telescope or microscope don’t outweigh the reduction in vision! This notion is also helpful in thinking through the negative implications of reduction. An AI-based application like ChatGPT for example, might amplify access to knowledge but at the same time reduce our critical thinking and our ability to know what is true or real.

Knowing that we live in a fallen world with sin and its consequences helps Christians to appreciate how people’s values and goals might influence the design of technology as well as our use of it. A simple and well documented example of this is how social media platforms use algorithms developed by AI, designed to appeal to our vices, rather than our virtues, to keep us engaged on the platform. The motivation for this is to sell more advertising that pays for the ‘free’ platform we use. As users of social media, we have a choice of how much time we spend, what rabbit holes we go down, how we interact and whether we allow ourselves to become addicted to it. Unfortunately, the platform design is set up to promote bad behaviour rather than virtue. Fake news is viewed six times more than real news, and many people become obsessed with their followers and how to keep the ‘likes’ up. This can lead to narcissistic behaviour and toxic postings, that are all too familiar on social media, leading to a greater polarisation of opinion. But why would companies and individuals develop and promote the use of such technology?

Significantly, much of the AI technology that has been developed in the West has been carried out by a relatively small number of Big Tech companies, like Amazon, Google and Meta. These and other large companies such as Microsoft and Apple, have the resources to acquire or invest in other specialist AI companies like Open AI and the British company Deep Mind. Since 2016, over 500 billion dollars have been invested in this sector so there is a huge vested interest in seeing it succeed. For the likes of Google and Meta, their business model depends on keeping the ‘user a product’, sucking in all their data, profiling users and selling this on to advertisers and others.

We are constantly told that this technology will benefit humanity by improving productivity and solving the problems of the world like health and climate change. Some go so far as to believe it might even lead us to the point where many won’t need to work and they will subsist on a type of Universal Credit. This techno-optimist worldview has now been adopted by many politicians who tell us that innovation and productivity are necessary for economic growth. There is also a fear of missing out which has led to an AI arms race with with many Western countries seeking to outdo China and come out on top. Vladimir Putin once famously stated that ‘whoever wins the AI race will control the world’.

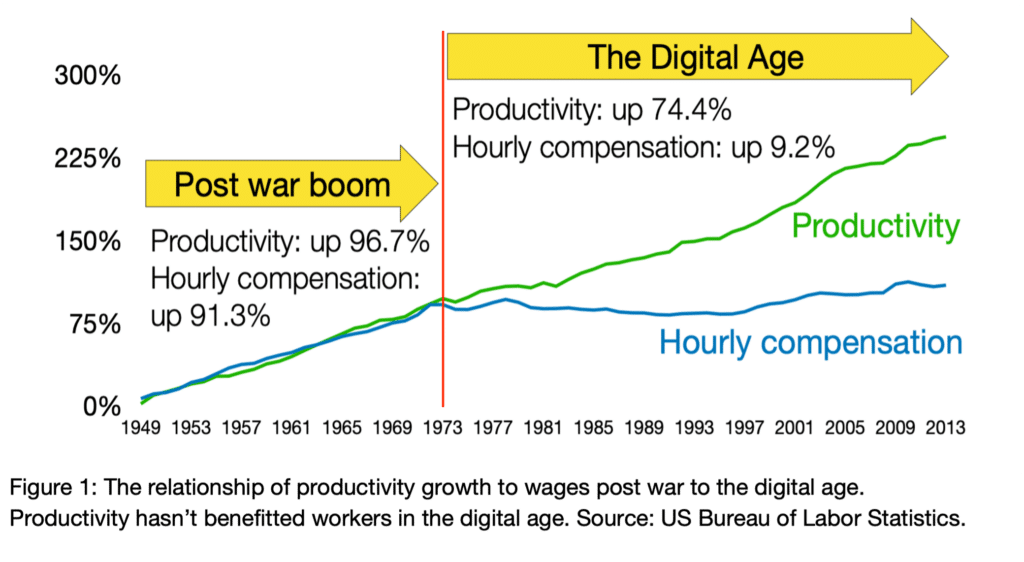

The reality for digital technology is however somewhat different, at least as far as its economic benefit to the general population. Figure 1 shows how the period between 1949 and 1973 in the USA, wages kept pace with increasing productivity.3 The years between 1973 and 2013, the digital age, saw productivity increase by 74.4%, yet the hourly compensation of workers rose by just 9.2%. During this period however, the median wage gap between the lowest and highest paid workers widened very significantly with the lowest decreasing to -5% and the highest increasing to 41%. In their book, Power and Progress, MIT economists Acemoglu and Johnson survey 1,000 years of technology progress and argue that it is mostly the elite and powerful that benefit from innovation.4 They cite the example of the Industrial Revolution to show that it takes pressure from ordinary people and government regulation to ensure that the economic benefits of improved productivity flow down to the workers. Automation in the 1980s displaced a significant number of blue collar workers. Today, AI applications are impacting white collar workers and professionals in all spheres spanning the creative arts, computer programming, marketing, accounting, the law and medicine along with office workers using Microsoft’s copilot, embedded in Office 365.

The gap between the hype about human flourishing and reality is not confined to the economic sphere. Digging beneath the claims surrounding AI capabilities in drug discovery, as an example, we find that, impressive though published results are for predicting known protein structures, there is still quite some way to go before the technology can predict structures that haven’t already been determined through traditional means such as NMR Spectroscopy or X-Ray crystallography. This is in part because proteins fold over time and according to context and these structures might not be well represented in the data set of solved protein structures used to train the algorithms.

We need therefore to be mindful of the agenda behind the promotion of AI applications like ChatGPT and many other similar capabilities. These companies care less about the impact on society and individuals than the profits that they seek to accrue and dominating the AI world. This shapes the design and marketing of these tools and how they are being deployed. The examples of social media, search engines, and even online shopping are instructive as the aim is to create an increasingly frictionless interface to the platform to encourage user engagement, to see more adverts or to purchase more goods. The more immersive the experience is, whether on a smartphone or tablet, the more users are sucked in and the more likely they are to become addicted.

Ironically, many of the leaders of AI companies have recently warned of the existential risks that advanced, so called Frontier AI, presents to humanity. So successful has this agenda setting been that the UK hosted the first global summit on AI safety in November 2023. Safety Institutes have now been set up by the UK and US with other countries likely to follow. Unfortunately, these institutes are too focused on addressing future risks rather than the here-and-now risks that AI applications are posing to society at large, through the way that they are shaping us. Neither are they adequately addressing the concerns that minority or marginalised groups have over specific risks, such as data bias, privacy and injustice from prejudicial automated decisions.

Although many, even Christians, think of technology as amoral or neutral, it is undeniable that tools have shaped our societies and societies have shaped the values and ideas of the people who design and sell these tools. We tend to give too little thought to these aspects when we enthusiastically embrace new technologies and inventions. Christians are then unwittingly shaped by the world around us, especially as the way that society uses technology is normalised and unquestioned.

Imitating Christ in a virtual world

Although the image of God in us is affected by our sin and desire for moral autonomy, Christ has freed us from slavery to sin. Paul exhorts the Christians in the church at Ephesus, ‘Therefore be imitators of God, as beloved children. And walk in love, as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God’ (Eph. 5:1–2). Paul also said to the Corinthian church that they should ‘Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ’, meaning that we should imitate Paul in so far as he reflects Christ. It’s essentially the same exhortation, imitating God and Christ is a command for us to image the Godhead, to allow the nature of God, in whose image we’re made, to shine forth.

In Paul’s letter to the Colossian church he urges them to ‘Put to death therefore what is earthly in you:’ listing some of the things we must put away ‘seeing that you have put off the old self with its practices and have put on the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge after the image of its creator.’ (Col. 3:1-10). The image of God in us, although tarnished by sin, is being renewed in line with the image of our creator. If we allow ourselves to become immersed in technology that diminishes the true image of God in us, we’re not cooperating with the Holy Spirit, who is the one who helps us to put off the old self and put on the new:

I appeal to you therefore, brothers, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship. Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect. (Rom. 12:1–2)

In his book on the Sermon on the Mount, John Stott makes this observation: ‘Probably the greatest tragedy of the church throughout its long and checkered history has been its constant tendency to conform to the prevailing culture instead of developing a Christian counter-culture.

We must pay attention to the impact that the world around us, including technology and AI, has on the renewal of our self, and our sanctification. We’re engaged in a spiritual battle against the forces of darkness and the devil will seek to subvert the process of our sanctification, our becoming more like Christ. Let us be careful that the convenience some AI applications offer us, or indeed any other technology, doesn’t become self seeking, the substitution of self for Christ in our affections, ‘which is idolatry’.

Asking the right questions

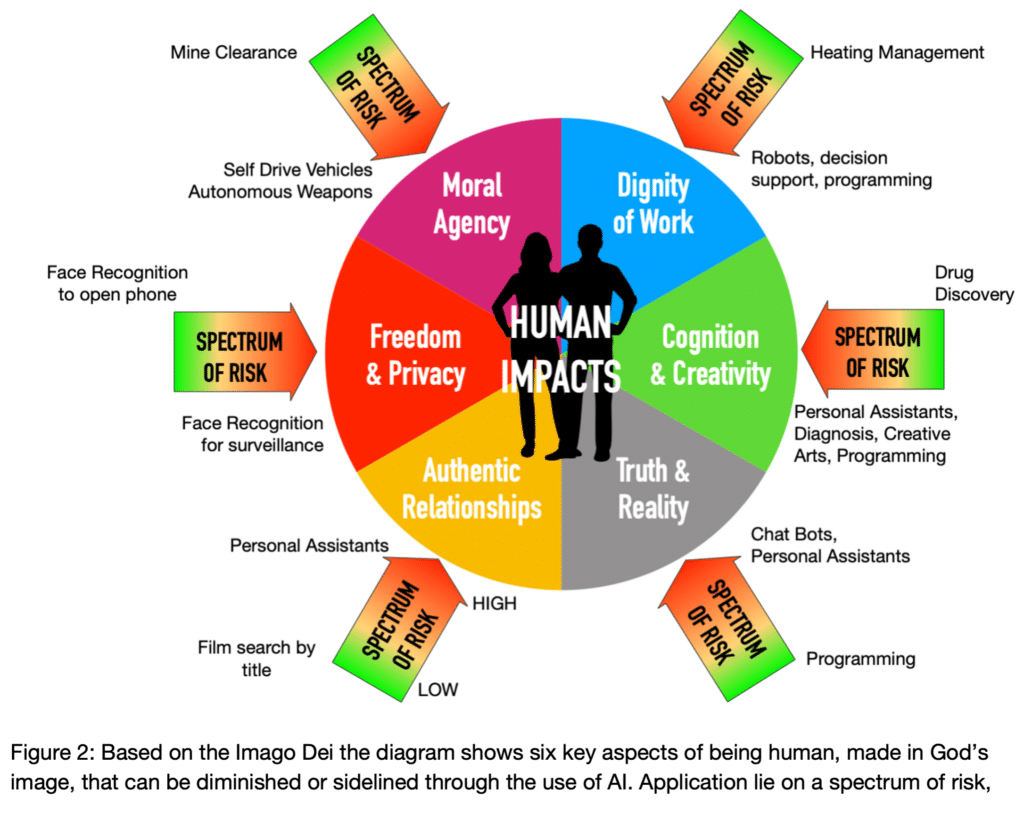

Although convenience and efficiency are not wrong in and of themselves, we need to balance what is gained and what is lost. We need to ask, what does this technology do for us and what does it do to us? Why are we using it, rather than something else? As we think about these questions it might be helpful to consider six key areas of our God given humanness, illustrated in Figure 2, that could be shaped by our use of AI applications, or indeed any technology.

There is a spectrum of risks associated with our use of AI, some applications will have no impact on our ability to faithfully image Christ in the spheres where God has placed us, whether church, friends, family or work. Other applications will have a significant impact so we will need to evaluate our engagement in each use case and think about how it will shape our behaviour over time as well as how our use will impact others and their view of Christ, who he is and what he is like. Many applications impact more than one of the six human areas shown in Figure 2.

One example of this is ChatGPT which can be used for writing stories, emails, summarising books or conversationally providing information. Some have adapted ChatGPT to provide explicitly Christian content such as sermons, study outlines, prayers and spiritual guidance. We might ask why are we using such tools rather than our brain and creativity or asking our pastor and friends for an answer to a question that we may have.

We are effectively giving up our creative activity and imagination, all for the sake of convenience. What is more important to God, using our brain, asking our pastor or friend for an answer to a question that we may have, or freeing up time? When we get an app to write a prayer for us aren’t we replacing seeking the Holy Spirit to give us words and listening to his prompting? Who is the author of that prayer, email or story that we get an app to generate? Or to put it another way, who is doing the ‘thinking’, it isn’t the AI artefact, it’s simply regurgitating sentences as a statistical amalgam of all the texts it’s been trained on with no attribution to any author or authors. Seen in that light, we need to ask ourselves whether we honour God and the creativity he has put in us by getting an artefact to do the work, to become a proxy author and thinker.

Such applications also impact human agency, when we outsource cognitive tasks we are effectively giving the artefact proxy agency, yet humans alone have been endowed by God with moral agency. We cannot delegate this to an artefact that cannot think or act volitionally. We are responsible for the output, its truthfulness or not and the impact of the output on others. The impact of Generative AI on truth and reality is illustrated in the case of a passenger who won a case against Canadian Airlines for refusing to honour the incorrect policy information that its chatbot had created regarding bereavement travel. The judge ruled that the company was liable for the accuracy of information on its website, whether produced by a chatbot or not. This is an inherent problem of AI systems that generate plausible but incorrect output, often called hallucinations or confabulations. An evaluation carried out by Algorithm Watch on the accuracy of answers generated by ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot on the Swiss elections in 2023 found that nearly a third of the answers were incorrect and another 39% were evasive. For Christians, there are further questions about how we view scripture, truth and the Holy Spirit’s work when we use statistical algorithms to summarise a bible book, to answer questions about the Bible or Christianity.

Privacy and freedom are also impacted by Generative AI applications that use Large Language Models (LLMs) that have been trained on texts and images harvested from the internet as they often include copyright material. Several lawsuits have been filed against a number of AI companies like OpenAI and Midjourney for copyright infringement of both text and artistic material. Notwithstanding their counterarguments of ‘fair use’, they have acknowledged that these capabilities would not have been possible without using copyright material and Sam Altman, Open AI’s CEO sought to get the UK to waive copyright law for LLMs. Using ChatGPT or any tools based on current LLMs, along with those that generate images or video, seems to me rather like singing songs at church without a copyright licence or acknowledging the copyright holder!

Using applications like Midjourney or Microsoft Copilot, will over time, shape the way we think about creativity, moral agency, authentic embodied relationships, privacy, truth and reality. Some companies have suggested that this technology will give everyone a personal assistant, except it’s not a real person with whom you can have an authentic relationship. The human activities that we replace, using such tools, will over time become detached from their uniquely human locus. Convenience will be the yardstick by which we judge this technology’s usefulness, rather than the moral question about how it’s shaping us and whether it’s helping or hindering us from becoming more like Christ, reflecting his image and leading us closer to God. Using a statistical tool to generate what is normally the creative process of humans is to abdicate our image bearing responsibility, dumbing down over time what it means to be human and robbing God of what he designed us to be and do.

What are the messages we are communicating to our church community when we use Midjourney to produce pictures to illustrate our sermon or an AI app to write a prayer or sermon outline and get a copilot to reply to emails? When we abdicate our responsibility to be like Christ in our homes and workplaces for the sake of convenience, we unwittingly communicate what we value to our children and work colleagues.

| Characteristics of true image bearing in authentic relationships | Influence of digital technology and personified AI | How am I being formed by AI and digital technology? | What are my choices? |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Table 1 gives some practical questions that we can ask ourselves about using applications that impinge on relationships, what they do to us and how they might be forming us, along with what we can do about it. Such questions can be developed for other application areas including those that don’t use Generative AI and that even are working in the background without our knowing, for example in credit checking or analysing our job application.

The more humanlike and convenient AI technology becomes, the more it erases the distinction between online and offline, while at the same time creating an illusion of more control of our lives and our digital world. Yet the evidence is that this technology is already beginning to control us. Children, for example, find it hard to take off the ‘lens’ through which they see and interact with the world. Digital technology, and increasingly AI mediated technology, is their world. Many have become reliant on this technology and are uncomfortable when it’s taken away, finding themselves insecure and struggling emotionally to deal with people face to face. It has become a mediator through which we interact with other people and through which we understand our world, it has become nothing less than a digital priesthood. Idolatry can be defined as anything that we value more than God, the things that drive us. When we replace our responsibility to image him by, for example, using an AI app to write a prayer or a story, are we not valuing convenience more than being a faithful witness?

Conclusion

We need to think about how to develop and deploy AI based technology that will serve humanity rather than simply race to replicate it. Applications of technology and AI in particular are best targeted at enhancing or extending human capabilities, rather than replacing them, amplifying something we can do but not reducing our humanity at the same time. An example is the use of robots in surgery where higher precision can be achieved than a well trained surgeon might be capable of due to the limitations of hand dexterity. We can use AI based robots in hazardous environments like finding and neutralising mines. The techniques used in AI, like Machine Learning (ML), might be able to perform tasks that humans can’t easily do, like finding patterns in data for fraud detection or cybersecurity. Generative AI and ML techniques are increasingly being used in ‘Digital Twins’ that are virtual models of real or intended physical systems and environments like wind turbines or manufacturing processes. These models have a role in improving the design and performance of many physical systems. AI might also be used to carry out tasks that would be impractical for humans, as they would take far too long, potentially speeding up scientific research in areas like drug discovery. Rather than replacing creativity and cognitive activity, AI applications might be better assisting in tasks, such as checking human generated software code to highlight potential problems, rather than doing the programming itself. These are just a few illustrations of how AI could be used to benefit, rather than sideline humanity.

As communities of God’s people, we can show the world a different way by modelling authentic community that is situated and embodied, where relationships are built on love not likes. We can show how God’s gift of creativity is valued and celebrated by involving others in the process, rather than sidelining them by using ChatGPT or Midjourney, and other similar technologies, to create devotionals or graphics for our church. Being intentional about encouraging one another demonstrates how true knowledge and wisdom are shared within our communities rather than obtained from a statistically based artefact trained on masses of data that has no thoughtfulness or ground truth. Truth is found through reading, studying and discussing God’s word in community and our knowledge and understanding of our world are mediated through reliable news sources, critical thinking and discussion with trusted friends.

These next few years will be challenging as more and more applications are released onto an unsuspecting world, infiltrating the public service arena, our workplace, our homes and even our churches. With God’s help and by his grace the church can make a difference, being the salt and light that we are called to be. May God grant us discernment as we navigate the rapidly changing world of AI and may he keep us from losing our saltiness, so that we are only fit for scattering on the ground and being trampled underfoot.

1 See: Affinity’s Social Issues Bulletin – Issue 53. Online: https://www.affinity.org.uk/app/uploads/2023/08/Issue-53-Summer-2023_final-WEB.pdf

2 See: Affinity’s Social Issues Bulletin – Issue 54. Online: https://www.affinity.org.uk/app/uploads/2023/11/Issue-54-Winter-2023_final-WEB.pdf

3 Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata from the CPS survey conducted by the Bureau of the Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics [machine-readable microdata file]. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.epi.org/publication/charting-wage-stagnation/

4 Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, Power and Progress, Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity, (London: Basic Books UK, 2023).

5 J. Stott, The Message of the Sermon on the Mount, revised edition (London: Inter-Varsity Press, 2020), p. 45.

Related articles

Stay connected with our monthly update

Sign up to receive the latest news from Affinity and our members, delivered straight to your inbox once a month.